The Felts Family

By Elinor Wright

Sue is out in the yard as Pam and Caryl and I drive up with the trunk full of fragile baby’s breath. We have been busy most of the day gathering and delivering. Well, hunting, gathering, and delivering. The best part is the delivering.

“Over here,” Sue beckons.

We walk through trees heavy with the smells of summer, our arms sprouting branches and tiny pink and white blossoms.

“Right here,” Sue calls again as we carefully place the flowers on the deck of the Felts’ cabin. This cabin is on high ground and intimate. It commands the rugged view of the lake toward Arrowhead (Starr) Island, willing its response to the whims and desires of those who live inside.

Many of our cabins are too far removed to hear the subtle sounds of the movement of the lake in early spring, the uneasy shifting, the shoving and flexing, the ominous moans and low groans followed by a sharp crack, a rifle shot of ice-crack killing winter’s hold on Wahatowongong, the Lake of Sandy Shores. The Felts’ cabin, however, is on a high bluff right above the shore.

“We don’t own the lake,” says Nancy, Sue’s daughter, “but this part, this Felts’ Bank, this is ours.”

Nancy is an almost-every-summer Minnesotan and has been for many years. She shows us the loft in the sleeping house they have recently remodeled to accommodate the growing families. Improvements. “The fact is,” Nancy explains, “we don’t want it to change much. The years twist one way and another, but here, this place, this remains a constant in our lives.

“Dad was such a magnet. Family and friends are drawn here. We have as many as 15 guests at one time – and they stay for several days. People don’t drive from Illinois or Colorado just to join us for dinner.”

Sue adds, “Yet this place adjusts and settles in to make all of us comfortable. Age doesn’t matter. Numbers don’t matter. It has always been like that. It has been like that for over 50 years.”

“My sister Sara feels that way, too.” Nancy gestures toward the lane, “The pines always welcome us into the driveway. They wave and sometimes they remember our names. ‘Sara – Nancy’.”

“Saaaara - Naaaanceeee.”

Sara is Nancy’s younger sister. Her family says she could walk these paths on a dark night without a flashlight.

They have heard the birches whisper sweet spring secrets to each other, rustling quietly as the sisters pass Meyers’ Corner.

Who among us has not been stirred by highflying Canadas gabbling overhead, the wild wailing loon, the lovely notes of a robin calling for rain? In that thin line between twilight and full dark there are silences so profound in their timing that one can hear the earth settle. On a late summer evening the birds are quiet, the fishermen are home, the grasses stop rubbing one another’s shoulders, the lake calms, the gossipy trees sign off for the day, and if you sit quietly there is silence, real silence, the kind where you can almost hear the blood coursing through your veins.

Nancy serves iced tea and rhubarb cake. She adds a lemon slice to each tall glass. Then, reflectively, she says, “Each summer when I return, it’s a reunion. I walk these well-worn paths and get reacquainted with the trees. I visit with them. I ask them how their winter was. They tell me things, show me new scars, like antler scratches and lightning strikes. They brag about a young shoot, or complain about a wound in the bark hammered deep by a pileated woodpecker. Then, when I’m not paying proper attention, the gnarled old basswood just off the trail breathes a wonderfully familiar fragrance on my face. I stop and take it in. ‘I missed you,’ I say. ‘I’ve missed you very much’.”

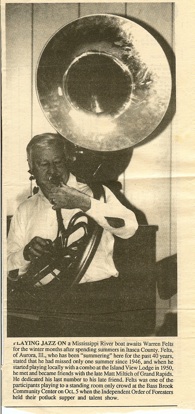

This is the Warren Felts’ family of musicians. Music busies and fills their lives. They perform, they teach, and they encourage young musicians. They talk a lot about music.

The youngest are the fourth generation of Felts’ to come to Sand Lake for the summers.

Why are they here? Maybe they need a break from musical demands, the schedules, the gnawing reminder that one more practice will make the performance even better. But maybe not. Maybe these musicians are drawn here by the rhythm of the sounds and the silences in this North Country. Have you ever been asked to stand still and listen when you didn’t hear anything? Picture this – It is the last week of August, and there is a low and heavy harvest moon, smoky orange and oval-shaped, hanging just above the trees on the opposite shore.

“Listen,” Warren was the kind of person who . . .

Finally we hear it, the high tremor of Indian song carried by the ebb and flow of evening water lapping, lapping, swelling in volume as the dusk thickens and dies away. We are on the Inger wave length. The Chippewa are celebrating a harvest of wild rice and give-away. The drums, the dancers, the high voices of the singers pow-wow their gratitude. The message is clear: “Meguitch. Thank you. It was a very good year!”

Sue recalls the early days of fishing when 6 o’clock p.m. meant that everyone should be on the water. Serious fishing was scheduled for 7 – 9 p.m. Often people became acquainted boat-to-boat. They would fish and visit and reel in a new friend in the process of stalking a walleye.

Indeed, that’s how Warren learned of Island View’s nice new dance floor and the possibility of an engagement for his dance combo. He talked with Milt Etsch, the proprietor of Island View, and landed a job for the summer of 1950. The combo consisted of three Aurora musicians: Jim Murphy on sax and clarinet, Eddie somebody on guitar, Warren Felts on string bass, and two musicians (a drummer, and an accordion player) from Grand Rapids. They played several nights a week at Island View Lodge sparking the Golden Age of Sand Lake Elegance with white linen dining and dancing lakeside until 2 a.m., a Tommy Bartlett Water Ski Show on Sunday afternoons and a chef from Chicago who had cooked for someone who had cooked for Al Capone or John Dillinger or Pretty Boy Floyd. (Not true in any case, but in every case, good for business.) People here loved to dance. Warren and his band played Finnish polkas and Scandinavian waltzes, but soon discovered that the dancers warmed up to ballroom dips and whirls as the band played “Deep Purple,” “You Made Me Love You,” or “It Had to Be You.” An evening of dancing generally ended with I’ll See You In My Dreams.

We asked to see Sue’s caning projects. She has been caning chairs for many years. She is a master caner, a fantastic cook, and a blessing to her children.

Warren and Sue brought their children here. They brought up their children here, too, in the way of the woods. Children’s memories include getting ice for the icebox from the ice houses at Chapel Hill or Cedar Lake Lodge, card games by kerosene lamplight, dreary days warmed by a fire in a potbellied stove, berry-picking, clearing trees with a two-man cross-cut and axe, leaky roofs, a cabin fire and a futile bucket brigade from the lake. They remember building a fire pit and the outhouse. They remember priming the water pump and hauling buckets of water to make pin cherry-blueberry jelly. They remember the hills between Chapel Hill and Spring Lake and the places a car might get mired up to its axels after a good summer rain.

They remember the evening settlings that are a metaphor for musicians who understand rests. Rests give form and meaning to the sounds that surround them. Rests tell you that something important has happened.

There is the full orchestra of the swamp on an April night. First, a few high soprano soloists piping in the peepers; then, the tremulous song of the faint at heart gradually gathering momentum and volume, then the tuning up of the bass section here and there and finally a full grand crescendo as they all join together. This was the music before we knew there was music.

Musicians hear the gurgle, gurgle around a swamped row boat, the whoosh wings of the mallard, the spank of the beaver’s tail and the drone of a horsefly in September. Musicians hear the heavy sighs of the Norways as they brace themselves for yet another summer storm. Musicians hear the songs.

Perhaps we are all musicians in degree.

Warren didn’t want this country to change. He feared the losses that came with paved roads, clear-cutting the forests, straightening the curves, shaving off the hills. He wanted no Felt-way Beltway on Loon Feather Lane.

He left us with a great admonition, “Lean into the music,” he said. “Listen slowly. It takes time to breathe it in.”

The years twist one way and another, but here, this place, this remains a constant in our lives.

Music busies and fills their lives. They perform, they teach, and they encourage young musicians. They talk a lot about music.